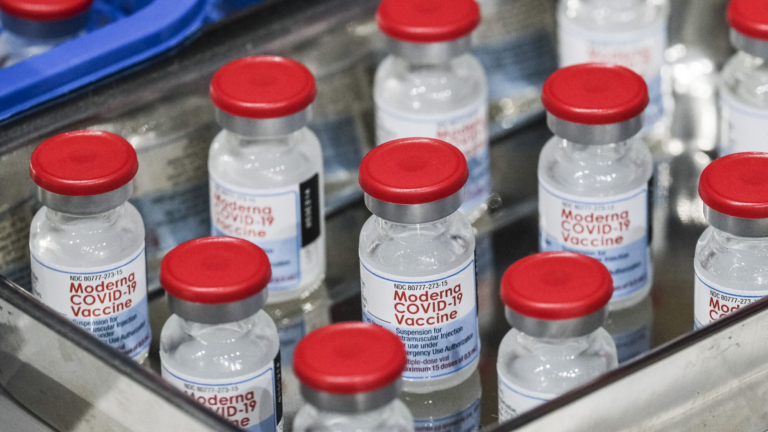

New vaccines could curb COVID variant, other viruses — if people can figure out when to get them

The vaccine campaign is rife with complications that include misinformation, higher costs for insurers, and confusion about who should get the new shots when.

Health officials are unveiling a new arsenal of vaccines to protect vulnerable Americans and exhausted health-care workers from an expected wave of COVID, flu, and RSV as the fall respiratory virus season begins.

An updated COVID booster should be available by late September. Flu shots are arriving at doctors’ offices. And for the first time, infants and seniors could be immunized against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), a persistent foe that public health officials had few ways to prevent.

But effectively deploying these shields is challenging and confusing.

“It’s absolutely overwhelming, especially for our patients,” said Sterling Ransone, a doctor in rural Virginia and board chair of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

The coming vaccine campaign is rife with complications that include higher costs for insurers and health practices because the federal government is no longer buying coronavirus vaccines for everyone — as well as outstanding questions about how to best time these shots, who is going to pay for them and other issues that can’t be addressed until all vaccines are formally approved.

Doctors have to figure out how to explain the nuances and unknowns of new vaccines at a time of rampant misinformation. Patients perplexed by changing coronavirus vaccine guidance now have more shots to consider. Public health officials worry a messy rollout could further erode confidence in routine vaccination and risk overwhelming the health-care system with preventable cases of RSV, flu and COVID.

“If we learned nothing else from the pandemic, public health credibility is everything in how people will take your recommendations,” said Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota. Clinicians need clearer guidance on how to space the shots and explain the risks of co-administering them, he said.

An annual vaccination

The updated COVID booster, designed for the XBB lineage of the coronavirus that became dominant this year, marks the shift from a staggered release of boosters to an annual vaccination for all age groups, similar to the fall flu vaccine. Officials say this approach would ease confusion about which Americans should be getting boosted and when.

But that plan has also drawn criticism because the coronavirus can surge in spring and summer, when immunity from a fall booster has waned, and evolve into versions a fall booster was not designed to target. That scenario is happening now as infections increase with a new subvariant — EG.5 — on the rise, and seniors and immunocompromised people weigh whether to get a second booster shot designed for the long-gone BA.5 subvariant or wait for the new one.

Some Biden administration officials have questioned whether approval for the updated COVID boosters could have been expedited given the recent uptick in COVID cases, according to three people with direct knowledge of internal conversations. COVID-related hospitalizations and emergency room visits have increased for the first time since the public health emergency ended in May.

Pfizer, one of the booster manufacturers, had said in June it could have begun distributing its updated booster by the end of July if regulators approved. But neither the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention nor the Food and Drug Administration have acted yet.

The FDA is expected to sign off on the updated COVID boosters by mid-September, according to officials familiar with the plan. The CDC’s vaccine advisory panel is expected to meet shortly thereafter to recommend who should get the shots — probably everyone 6 months and older. Babies under 6 months are assumed to have antibodies passed along from their mothers. CDC Director Mandy Cohen has said the vaccines should be available for most people by the third or fourth week of September.

‘The messaging needs to be clear and simple’

Don Wind, a 67-year-old Texan who is more attuned to the vaccine campaign than the average American because he regularly reads COVID news and listens to health policy podcasts, struggled to figure out when to get his next booster. Wind had his last coronavirus shot in November and delayed getting another one ahead of his vacation to Cape Cod in August, thinking the release of the updated formula was imminent.

He tested positive for COVID on Sunday, forcing him to cancel the second leg of his vacation in New York. He said he wished the CDC had provided a clearer timeline for vaccination and made updated vaccines available earlier if the manufacturers were ready to distribute them.

“The messaging needs to be clear and simple and ubiquitous,” Wind said in a phone interview while he washed clothes he had sweat through in the middle of the night.

This will also be the first time the federal government is not buying all the coronavirus vaccines and distributing them free.

A federal program to provide free shots to uninsured people at pharmacies probably won’t launch until mid-October, the CDC has said. While it will be free to consumers with health insurance, doctor’s offices and other vaccine administrators will be on the financial hook for securing them and hoping there’s enough demand to get reimbursed. Demand for coronavirus vaccination has declined since they first became available, with fewer than 1 in 5 Americans receiving the last booster.

Another messaging challenge ahead is how COVID boosters should be administered alongside a flu shot and a new RSV vaccine for people over 60 years old. There’s a tension between providing maximum protection vs. maximum convenience. The ideal timing for a COVID booster varies for each person, depending on when they last received a booster, were infected with COVID or want to maximize protection.

A flu shot is usually recommended before Halloween, ahead of the usual flu season. And RSV vaccines are best administered as soon as possible. But three visits to the doctor or pharmacy for shots could be unfeasible, especially for seniors with mobility issues or poor access to health providers.

“Will that be seen as overly onerous to get three shots and will that discourage people from getting vaccinated?” said Celine Gounder, an infectious-disease specialist at Bellevue Hospital in New York and editor-at-large for public health at KFF Health News. “We should make it as easy as possible for these elderly patients to come in and get all three if they want to and also to space them apart if they want.”

The CDC says it has not seen data suggesting safety concerns co-administering COVID and flu shots, which could improve uptake of both vaccines. But clinical trials for the RSV vaccines found rare instances of severe side effects in people who received an influenza vaccine at the same time. It’s unclear if it was a statistical fluke or a consequence of co-administering the vaccines. Still, providers must weigh the potential for rare side effects against the potential harm of seniors contracting a severe case of a virus they are not vaccinated against.

Health officials and clinicians worry any negative effects, no matter how rare, will be weaponized to fuel vaccine skepticism amid increasing anti-vaccine sentiment, especially around the coronavirus vaccine, and make it even more challenging to convince consumers of the benefits of another COVID shot.

Mike Silverstein, a 75-year-old D.C. resident, said he’s eager to get vaccinated for RSV, which he believes he contracted last fall when he developed a respiratory infection that left him bed-bound for several weeks and coronavirus tests came back negative. But he’s also leery of overlapping vaccines after a bad reaction to receiving a bivalent booster and an mpox vaccine one day apart last year.

“We are with some of these things in uncharted territory,” Silverstein said. “The most important thing the public health service can do is tell people there are things that we don’t know and be honest and up front about that and let people make the best decision they can.”

Health officials say maintaining public trust is critical because the new respiratory virus vaccines can save lives if widely administered. The CDC estimates the annual death toll from flu ranges between 12,000 and 52,000, and RSV kills between 6,000 and 10,000 seniors and 100 and 300 young children each year.

“In years past, we simply accepted that,” Joseph Kanter, Louisiana’s top health official, told reporters last week. “COVID made us realize that when you have protections out there, you should do your best to make sure they are utilized because those lives can be saved.”

Ask your doctor

The CDC has not recommended all people over 60 years old be vaccinated against RSV. Instead, the agency advises people to consult with their doctor about individual risk factors to determine whether to get the vaccine.

But that may leave out many consumers who should get the vaccine but don’t have regular access to a health-care provider, said Camille Kotton, clinical director for transplant and immunocompromised host infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Black people and Native Americans get infected with RSV at significantly younger ages than Whites and Asians, she said. “So we worry that people who need it most may not be getting it,” said Kotton, a member of the CDC’s vaccine advisory panel.

There are similar challenges around equitable distribution of the RSV immunization for infants. Nearly every child is exposed to RSV but the virus is more likely to cause severe disease in infancy when the baby’s airways are smaller.

Children’s hospitals and pediatric offices were slammed by a surge in RSV cases last year. Officials hope that wave was an anomaly caused by unusually high levels of susceptible children who were not previously exposed to RSV while their families took COVID precautions.

Earlier this summer, the FDA approved the monoclonal antibody treatment Beyfortus that acts like a vaccine by protecting against severe disease for a single RSV season. The CDC in August recommended the treatment as an immunization for infants under the age of 8 months and young children up to 19 months who are at risk for severe disease.

But the drug manufactured by AstraZeneca and marketed by Sanofi is expensive — at $495 per dose. It’s unclear if insurers or the Vaccines for Children program for low-income families will be prepared to cover the costs ahead of the upcoming respiratory virus season, which usually starts in the fall and peaks over the winter.

Sandy Chung, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said cash-strapped pediatric offices would have to pay for the costs of the treatment up front and hope enough are used and reimbursed to avoid financial losses. They’ve faced similar challenges with unused flu shots and also have to weigh whether it’s worth buying updated COVID shots when booster rates in children are low.

“As pediatricians we want to save babies, we want to prevent kids from going into the hospital, but what is being asked of us just isn’t financially feasible,” said Chung, who is also chief executive of Trusted Doctors, a pediatric physician group in the D.C. area. “If your pediatrician can’t afford it, then the people to look to are the manufacturers and our health-care payment system.”

A maternal vaccine for RSV is still awaiting regulatory approval but could go on the market this fall. The manufacturer Pfizer has previously released data showing administering the vaccine during the third trimester of pregnancy reduced the risk of severe RSV illness in infants.

Claire Hannan, executive director of the Association of Immunization Managers, said it’s difficult to deploy the new RSV immunizations for this upcoming respiratory virus season when questions remain about costs and how to administer them – issues that can’t be sorted out until the immunizations are formally approved by federal regulators.

She faulted the federal government for not better preparing states to vaccinate their residents by providing advance notice of storage and handling requirements and dosing, as it did for the initial coronavirus vaccine rollout.

“It’s very beneficial to be at the table and discuss some of the planning and the decisions being made than be informed afterward,” Hannan said.

The Washington Post’s Dan Diamond and Laurie McGinley contributed to this report.

Conversation

This discussion has ended. Please join elsewhere on Boston.com