Extra News Alerts

Get breaking updates as they happen.

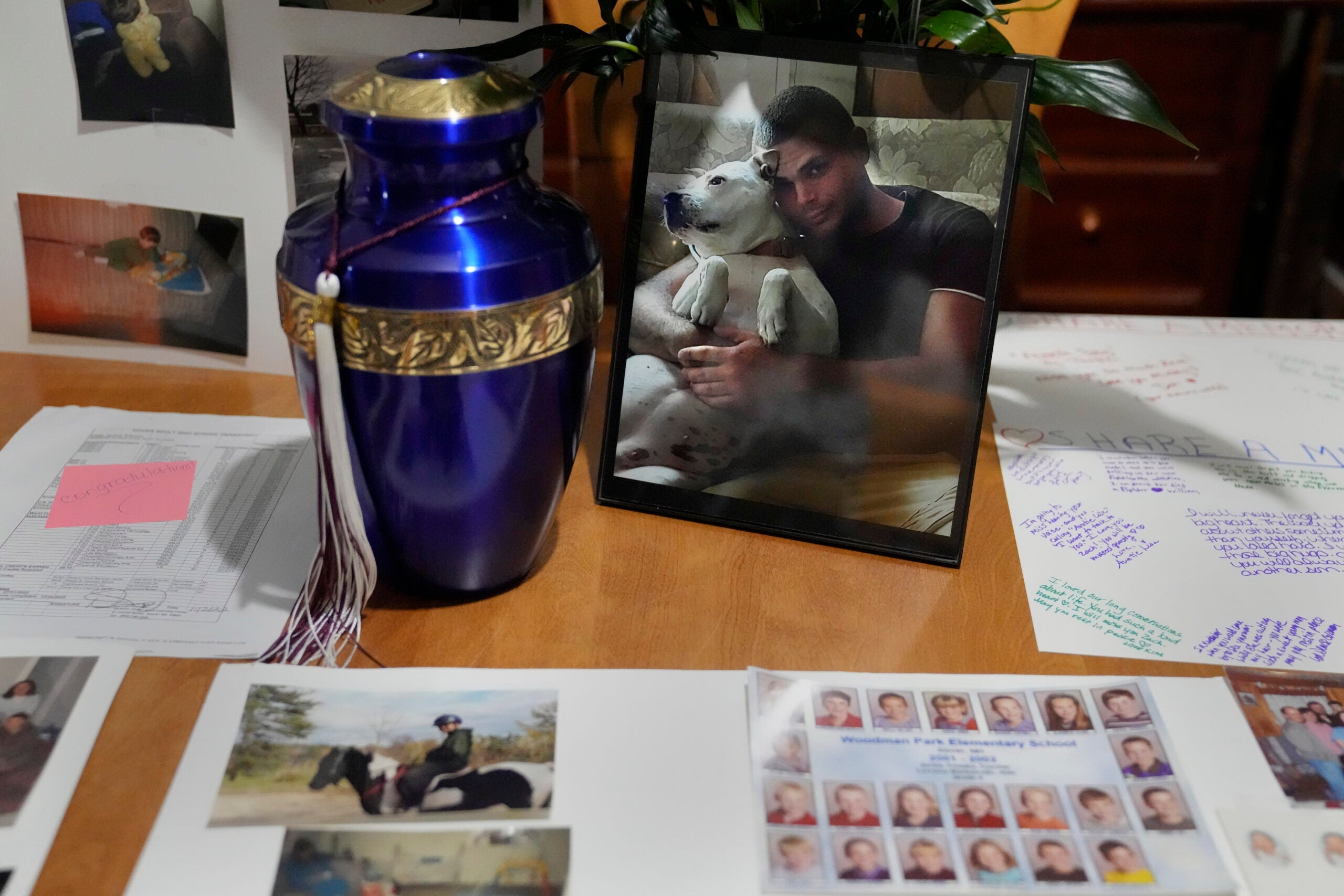

CONCORD, N.H. (AP) — Zach Robinson spent decades trying to fight off nightmares about being raped as a child at New Hampshire’s youth detention center. He died last month, still waiting for accountability for his alleged abusers.

“I know that I’ll never forget about what happened,” he said in early 2021. “But just knowing it’s out there and getting the relief of getting it off my shoulders I hope will limit the amount I re-live it.”

More than a thousand men and women allege they were physically or sexually abused as children at the Sununu Youth Service Center between 1960 and 2019.

But only 11 men have been arrested, none in the last 2½ years, despite a state police task force investigation stretching back more than four years.

Authorities cite the statute of limitations as one reason for the lack of further arrests. Yet hundreds of cases remain eligible for possible prosecution, according to an Associated Press analysis of 1,100 lawsuits.

While New Hampshire’s statute of limitations for most felonies is six years, it extends longer in sexual assault cases involving children. In those cases, charges can be brought until the victim turns 40 years old.

At least 356 lawsuits have been filed by plaintiffs who allege sexual assault and have yet to turn 40. Not all of them identify alleged perpetrators by name, but the 242 who do accuse dozens of staffers, nearly all of them at the youth center but some at group homes and residential treatment centers with state contracts. At least a dozen more turned 40 this year, putting their cases out of range for criminal charges.

“It definitely angers me but it goes hand in hand with how the operation of that place worked,” said William Grant, 38, who alleges he was abused by multiple workers in 2001 and 2002. “A lot of things were swept under the rug.”

___

The allegations out of the Sununu Center are horrifying: Former residents say they were gang raped, beaten while being raped and forced to sexually abuse each other. Staff members are accused of choking children, beating them unconscious, burning them with cigarettes and breaking their bones.

The scandal came to light after two former workers were arrested in 2019 and charged with abusing a former resident who had gone to police two years earlier. The first lawsuit was filed the following year, and by the time nine more workers were charged in 2021, more than 300 alleged victims had come forward. The first criminal trial is scheduled for April, while the first trial on the civil side is set for September.

Attorney General John Formella’s office declined to discuss The AP’s findings, the investigation or whether more charges are coming. Instead, a spokesperson offered a general statement confirming that the investigation remains active and pointing to the challenges of prosecuting sexual assault cases dating back decades.

“There are legal considerations that must be reviewed as to each specific case. Further, the passage of time makes it difficult for investigators to obtain corroborating evidence and some prosecutions may be barred by the statute of limitations,” said spokesperson Michael Garrity.

Attorney Rus Rilee, who represents the vast majority of those suing the state, said all of his clients want to see perpetrators prosecuted and are getting more angry as time goes by.

“While I fear that Attorney General Formella is going to continue to forego criminal prosecutions in order to avoid creating additional civil liability for the state, our clients fully expect him to do his job and prosecute their abusers while there is still time,” he said.

But another attorney who has both prosecuted sexual assault cases and represented victims said further charges are unlikely.

“These cases get worse over time. They’re already stale cases, so after two and a half years, I wouldn’t hold my breath for additional arrests,” said Neama Rahmani, a former federal prosecutor and president of West Coast Trial Lawyers.

Child sexual assault is both under-reported and under-prosecuted, and studies show fewer than 10% of perpetrators are ever brought to justice, he said. Prosecution is difficult when allegations go back decades, and the existence of civil lawsuits makes it easy for defense attorneys to argue that victims are lying to make money, he said.

“Prosecutors are risk averse,” he said. “If there’s any risk of losing, they just don’t bring the case.”

___

Many of the former youth center workers have multiple accusers, including Anthony Paquet, who is named in 93 lawsuits. While most allege physical abuse outside the statute of limitations, he’s also accused of sexually assaulting nine men who have yet to turn 40, including one who says Paquet molested him a dozen times.

Paquet, who retired in 2018, declined to comment on the allegations, according to a lawyer who represented him in 2021 when he unsuccessfully sought compensation for injuries he claimed to have suffered while restraining a teen.

Another longtime worker, Richard Croteau, is named in 82 lawsuits, including 12 still within the statute of limitations for sexual assault. Several possible phone numbers for Croteau were out of service. He did not respond to a letter sent to his home, and no one answered the door when a reporter visited in early December.

Croteau’s accusers include a woman who says he raped her in the facility and his vehicle, molested her every night for two weeks and threatened that she would be “dead” if she told anyone. In another lawsuit, Croteau is accused of raping a teenage boy in a ski lodge bathroom during a field trip.

The accuser in the latter case, Jacob, said when he spoke to police several years ago, investigators told him Croteau’s name had come up a lot.

“He was the worst one,” he said in a recent interview. “He gave off that old grandpa ‘you can always come to me’ type personality, and then the closer you got to him, the more he would push boundaries.”

The AP does not identify people who make allegations of sexual abuse without their consent. Jacob, who remained anonymous for an earlier interview in 2021, said he is now willing to go public with his first name and image because he is frustrated that so few perpetrators have been held accountable.

“I am at the point where I want the state to be responsible,” he said. “I want people to know.”

Another man who accuses Croteau of sexual abuse described him as a “vile man” who told him no one would believe him if he complained.

“I’d really like to sit across from him and say, ‘Remember me? I’m not that little boy no more,’” said William Grant.

Like Jacob, Grant said he wants his name to be used publicly to try to spur action.

“I was a number in there, I don’t want to be a number now,” he said. “My name is William Grant, and you can put it in bold lettering.”

____

The youth center, which once housed upward of 100 children but now typically serves fewer than a dozen, is named for former Gov. John H. Sununu, father of current Gov. Chris Sununu. Lawmakers have approved closing the facility, which now only houses those accused or convicted of the most serious violent crimes, and replacing it with a much smaller building in a new location.

Meanwhile, the mother of Zach Robinson, who died Nov. 3 of an apparent drug overdose, plans to use any money she gets from pursuing his lawsuit to open a sober living home focused on mental health.

“He struggled with addiction because of what happened to him when he was younger,” said Trina Cotter, who wears a pendant holding some of her son’s ashes.

Cotter said her son worked hard to get his high school equivalency degree last summer and wanted to go to college. But his success didn’t last.

“He always felt victimized and not worthy. He kept looking for things to make him happy,” she said. “And I think the people that were there to help him weren’t helping him. They were harming him all they way up ’til the day he died.”

Get breaking updates as they happen.

Stay up to date with everything Boston. Receive the latest news and breaking updates, straight from our newsroom to your inbox.

Be civil. Be kind.

Read our full community guidelines.