Newsletter Signup

Stay up to date on all the latest news from Boston.com

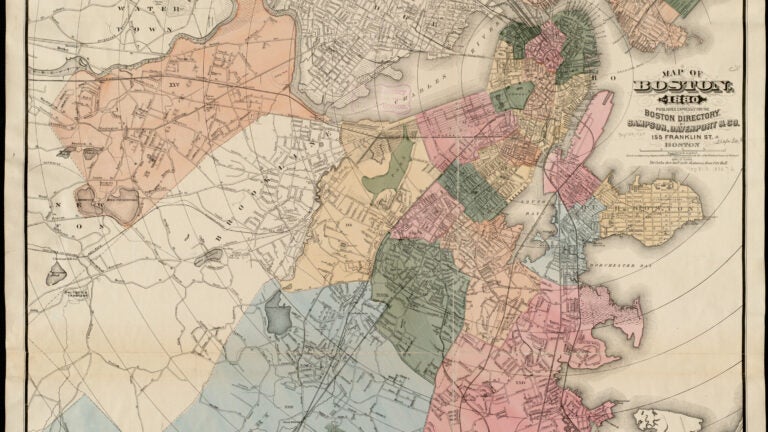

Pull out a map of Boston, and you’ll notice a conspicuous Brookline-shaped gap in the city’s borders, an independent island of suburbia floating just between Brighton and West Roxbury.

As Universal Hub put it, Brookline is “shaped like a paramecium surrounded by a Boston-sized amoeba.”

But while Brookline may seem like a glaring omission from Boston’s city limits, it didn’t start out that way. Before the Kennedys called Beals Street home, before the Coolidge Corner Theatre’s marquee bathed Harvard Street in neon light, Brookline was the hamlet of Muddy River, an outlying settlement and part of the larger city.

So, what happened? Why isn’t Brookline part of Boston today?

The simple answer dates back to 1705, the year Brookline was incorporated as a separate entity. But the town’s true battle for independence came in the 1870s, when Brookline spurned Boston’s attempts at annexation and cemented a certain singularity — and superiority, some would argue — that persists more than a century later.

“Here then, is a town within a city!” high school student Helene Bennett crowed in an essay published in the Brookline Chronicle in 1926. “A town, which, by maintaining a strict individuality, … has reached the highest standard of municipal excellency, in spite of the nearness of a great metropolis vexed and groaning under the better vicissitudes of the typical American city government.”

By the 1800s, Brookline was coming into its own as a prominent suburb that attracted “a galaxy of the rich and famous,” as historian Kenneth T. Jackson put it in “Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States.” Cabots, Lowells, Gardners, and Olmsteds were among the elite who would eventually call Brookline home.

The community had come a long way since Bostonians began using the area around the Muddy River for pasture in the 1630s. The two decades between 1840 and 1860 alone saw Brookline’s population grow by nearly 400%, according to Michael Rawson’s book, “Eden on the Charles: The Making of Boston.”

Suburbanization began in earnest around the 1840s, kickstarted by new developments in transportation and real estate, explained Ronald Dale Karr, a retired reference librarian and author of “Between City and Country: Brookline, Massachusetts, and the Origins of Suburbia.”

Railroads and omnibuses provided easier transportation into Boston, making it possible to live in Brookline and work downtown without access to a private carriage or stables. The 1840s also brought the first residential subdivisions, while an influx of Irish immigrants introduced a new workforce to build up the town, Karr told Boston.com in an interview.

Ultimately, the fledgling suburb held a lot of curb appeal.

Brookline “kept a lot of the advantages of living in the country — living among trees and winding roads, and things of that sort,” Karr said. “At the same time, Brookline showed that you could have some urban areas as well. Beacon Street is a continuation of the city, but it’s not the city. And what’s really not the city is when you go a few blocks from Beacon Street and you can still see large houses on individual lots.”

Of course, not everyone was satisfied with the status quo.

In 1871, several residents petitioned the state Legislature to join Brookline with Boston, which had recently annexed Roxbury in 1868 and Dorchester in 1870. According to Karr, state lawmakers agreed to the request — provided, however, that Brookline and Boston voters approved.

At the heart of Brookline’s annexation debate is an issue that still plagues the town today: Real estate development.

“Annexationists contended that Brookline’s destiny was being thwarted by its outmoded town government, controlled by a cabal hostile to growth and progress,” Karr wrote in “Between City and Country.”

Among this group were old Brookline families and property owners in the parts of town near Boston, who hoped that annexation would spur development and boost the value of their land. Their campaign focused largely on what the city could offer in terms of municipal services.

“The argument they use is that, ‘Hey, we can’t, as a town, get the resources we’re going to need if we’re going to become part of the metropolitan area,’” Karr told Boston.com. “In other words, we’re not going to have water, we’re not going to have sewers, we’re not going to have what people in Boston are getting right now.”

Their opponents included an unlikely alliance of commuters, Boston Brahmin families, and Irish American laborers.

Addressing the latter category, Brookline Historical Society President Ken Liss said: “The annexationists would argue that the people who were opposed to annexation told [the Irish American laborers] how to vote, but in fact, it’s more likely that the Irish Americans kind of knew that their access to the kinds of jobs available to them — working for the town on various projects — might be lost if that local control was given up.”

Opponents of annexation liked the town’s narrow country roads as they were and weren’t eager to exchange them for broad, urban avenues, according to Rawson.

“Most were not against growth, but they preferred low-density residential development, and they trusted the town to control it,” he wrote in “Eden on the Charles.”

William A. Wellman was the first to cast a ballot against annexation when Brookline went to the polls on Oct. 7, 1873, and the Brookline Independent reported that his face beamed “with the brightness that only illumines the countenances of those who know they have done right.”

Brookline’s final tally, per the Independent, was 299 votes in favor of annexation and 706 against. Three other communities — Brighton, West Roxbury, and Charlestown — also went to the polls that day for a vote on annexation and chose differently.

“On the same day that Brookline said no, they all said yes,” Liss said. “That didn’t take effect until 1874, but with Brighton and West Roxbury joining Boston, that’s kind of what made Brookline sort of an island. The only part of Brookline that was not bordering on Boston was kind of to the southwest, where it bordered on Newton.”

Annexationists made a few other attempts to merge Brookline with Boston through 1880, though their campaign proved less and less effective as the town developed public resources to rival Boston’s.

By the 1890s, Karr said, “Brookline was becoming an example. It was being used as a poster child for what the ideal suburb was supposed to be.”

Boston eventually got its hands on some of Brookline’s land in 1874, when the town gave up a strip along the Charles River so that Brighton could be linked to the rest of the city.

However, Brookline’s rejection of annexation the year prior set an example for other suburbs around the U.S. and “signaled the beginning of a national movement away from urban consolidation,” according to Rawson.

Today, at 63,191 residents, Brookline remains the largest town in Massachusetts by population as of the 2020 U.S. Census. Debates over real estate development and the town’s suburban identity rage on, echoing the rhetoric that once filled the pages of the Independent and the Chronicle.

“Brookline has, for a very long time, been very good about arguing,” Liss said with a chuckle.

Throughout the town’s history, he noted, there have been several examples of resistance to change and new kinds of development in town.

“And we see that today,” Liss said, citing the debate leading up to a recent Town Meeting vote on a rezoning plan. “So some of these issues, the more things change, the more they stay the same. But I think as with anything in politics — and in life in general — there’s a lot of back and forth, and there are a lot of people who have different views about the way things should progress. Sometimes for very good reasons, sometimes not for good reasons.”

Karr agreed. “There is a lot of continuity,” he said. “I think we tend to neglect how much the past influences us.”

Stay up to date on all the latest news from Boston.com

Stay up to date with everything Boston. Receive the latest news and breaking updates, straight from our newsroom to your inbox.

Conversation

This discussion has ended. Please join elsewhere on Boston.com